What inclusion really looks like beyond policy and programs

At the HR Inclusion Tour, I shared my story as a gender-fluid parent to a neurodivergent child, and why inclusion must start with safe spaces and a commitment that outlives initiatives.

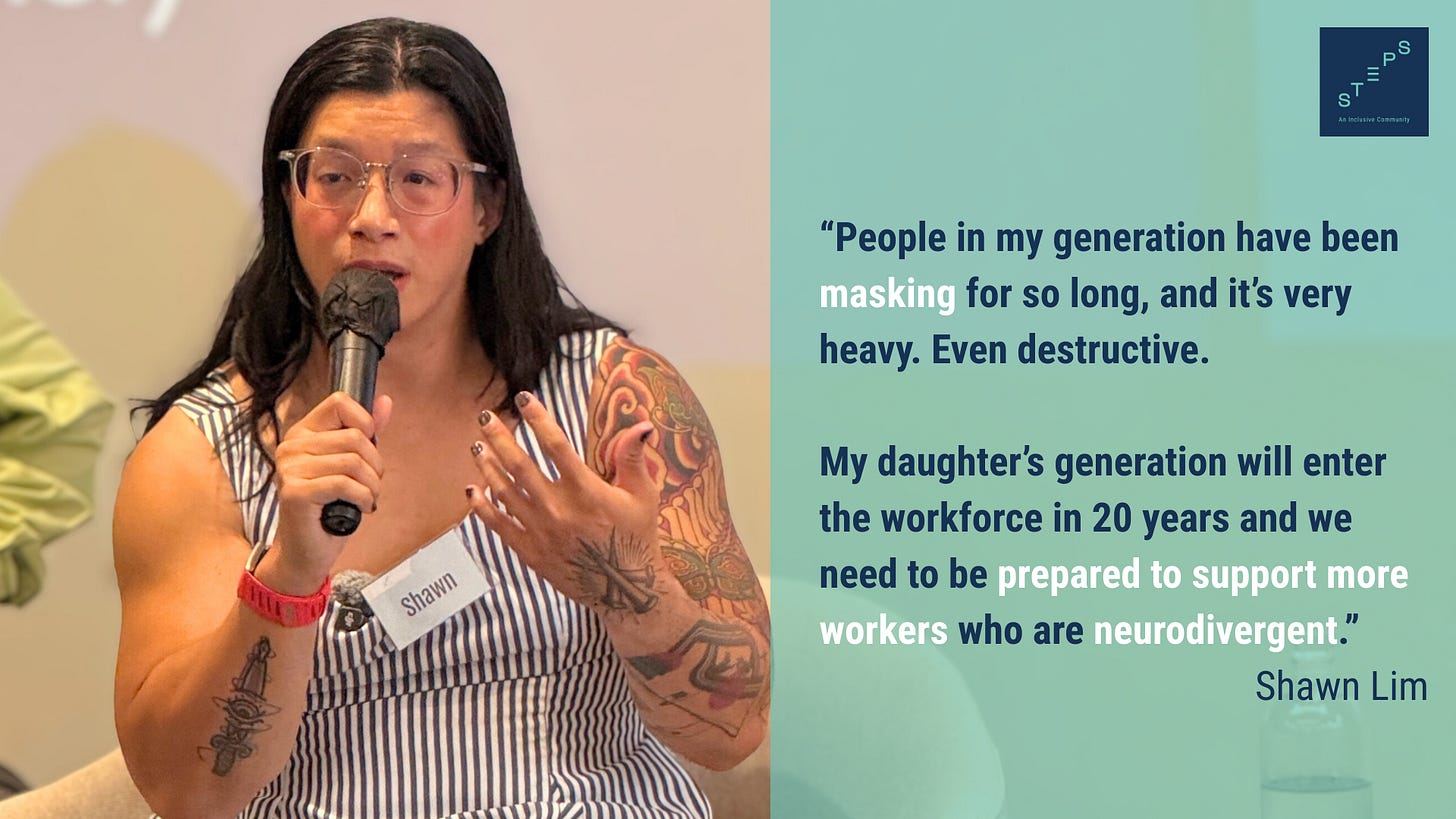

I had the honour of speaking on the panel “What Inclusion Looks Like – Real Voices, Real Change” organised by Steps two weeks ago.

I shared parts of my story as someone who is gender-fluid and non-binary, and as a parent of a three-year-old neurodivergent daughter who is currently in early intervention.

These identities are not abstract labels to me — they are lived realities that shape how I navigate the world and the workplace.

One of the key points I raised was that inclusion has to begin with space before it begins with programs. Bathrooms are one of the simplest but clearest examples.

Without safe, gender-neutral spaces, people like me are left with uncomfortable choices that signal exclusion, not inclusion. Companies must first create spaces where people feel they belong before implementing diversity initiatives that can otherwise seem hollow.

I also highlighted that sustainable inclusion requires clarity of capacity. Some organisations start resource groups or inclusive hiring schemes without considering whether they can maintain them. When these programs are deprioritised or dissolved, it leaves people in limbo. Inclusion cannot be temporary — it must be embedded into culture.

From my experience with my daughter’s therapy, I drew parallels to the workplace. Her progress depends on collaboration between therapists, teachers, and parents. Likewise, workplaces must recognise that multiple environments shape people, and inclusion means seeing the whole human, not just their work persona.

I spoke about the reality that many neurodivergent people carry overlapping conditions — autism alongside ADHD or OCD, for example — and how employers need to move away from seeing people as boxes that fit neatly into single labels.

Finally, I raised the fact that in Singapore, once someone is diagnosed as neurodiverse, that label stays in their health record for life. While this helps provide continuity of care, it can also create fear for parents. Add to that the long waiting times for early intervention, and it is clear that our systems still create barriers to timely support.

Yet the rising number of diagnoses also means the future workforce will see many more neurodivergent individuals. Companies cannot wait until then to act. The time to build inclusive cultures is now.

The message I wanted to leave the room with is simple: when people hide who they are, organisations lose trust, energy, and creativity. When people feel safe to show up fully, businesses and communities evolve.

Yes, labels are used for a reason, not only medical, but to mark someone as different. People often dislike differences, as they can disrupt the system. To maintain safety, we label and compartmentalize individuals, thereby preserving the status quo and avoiding challenges to it. Consequently, anomalies are often viewed as outliers.

What's helpful in your narrative is that you give a few distinct examples that people can relate to. Not to challenge people or the status quo, but to help frame identity in the context of a strict society of SG. People need that help without being threatened. Conversely, outliers need the same, and ironically, it's not seen.

I see a similar analogy of white privilege or any other race that isn't a minority. Those who have it don't often see it.

It doesn't mean one has to raise a Black Lives Matter flag; it does make me aware of how to live with others.